Fish Report for 11-8-2021

New SF Bay Releases Far Out Survive All Other Releases

by John McManus

11-8-2021

Website

Tagged salmon tell a powerful story

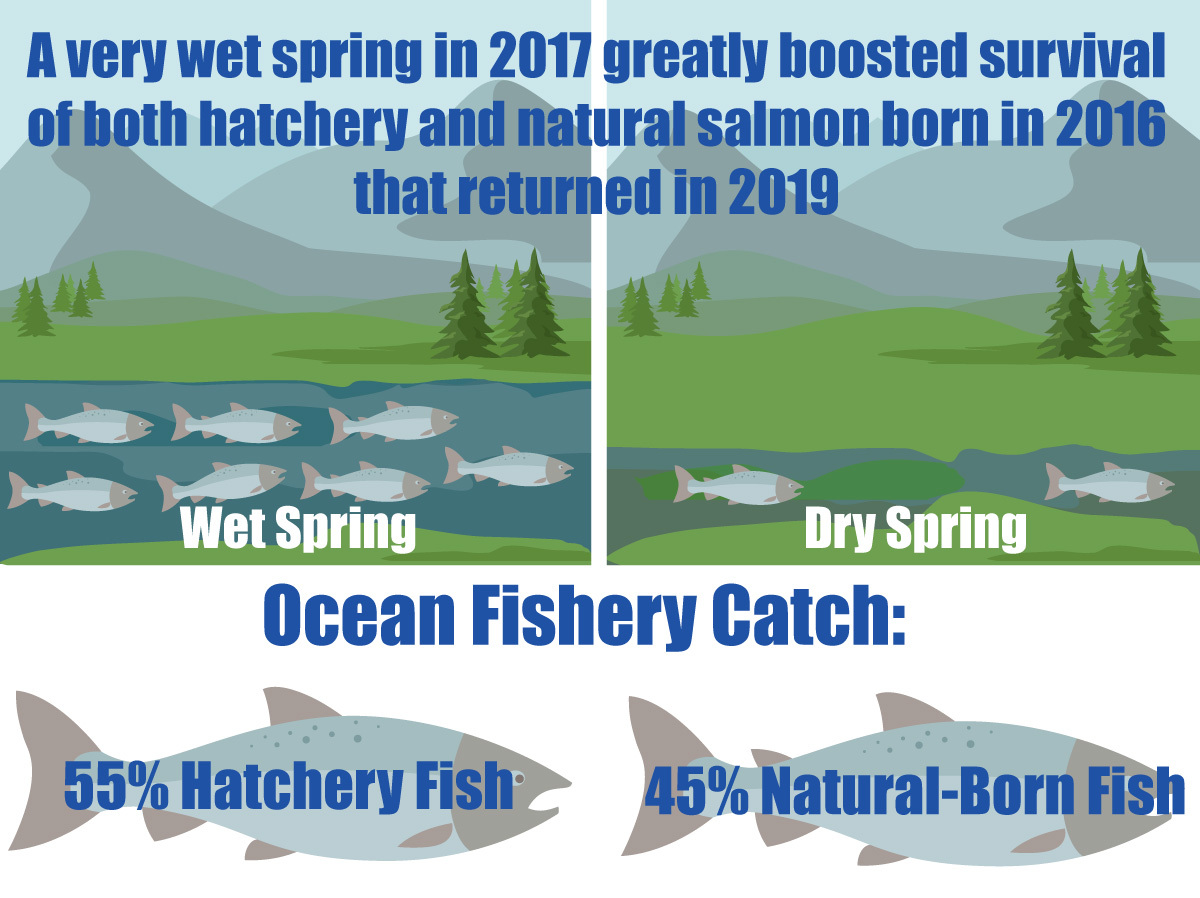

The California Dept of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) has released a report analyzing returns and harvest of the state’s 2019 Central Valley salmon runs. This is the most recent year data has been collected and analyzed for. The report deals mostly with three-year-old adult salmon born in 2016 which migrated as one year olds to the ocean in the very wet spring of 2017. In addition to three year olds, the report also includes data on two and four year old salmon that were caught or returned to spawn in 2019.

The bulk of the data comes from the tagging program where roughly 25 percent of the hatchery salmon produced in California are fitted with tiny tags that allow them to be identified later in life. Most of these tags are read after the fish reach adult size and are either caught in the ocean or inland fisheries, or their carcasses are recovered in Central Valley spawning grounds.

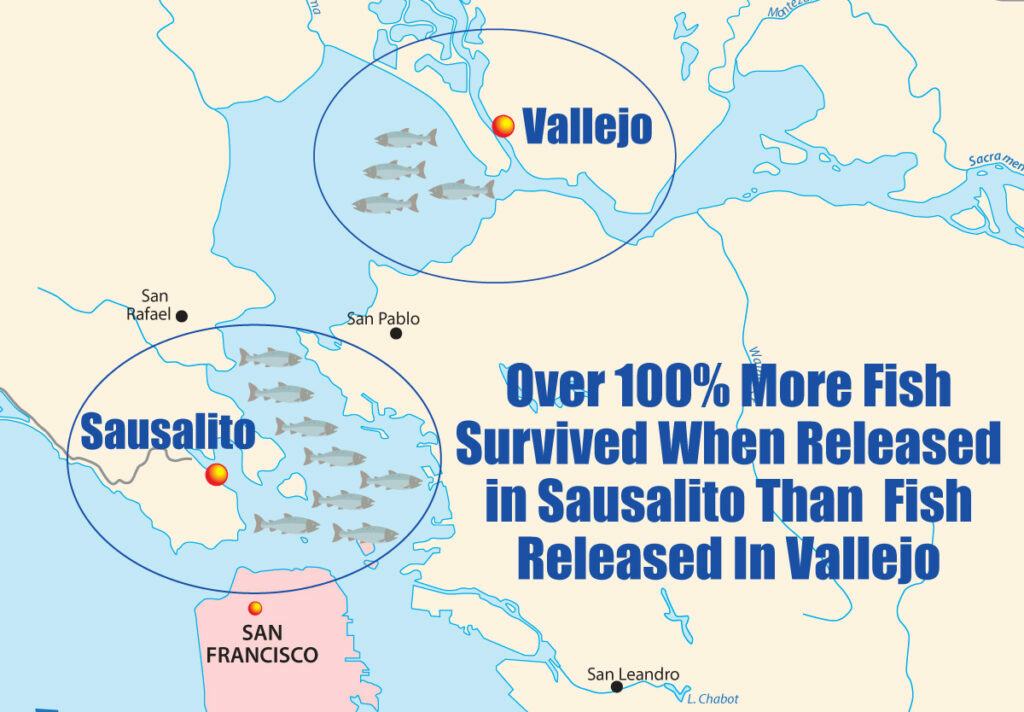

The single biggest takeaway from this report is the incredible boost in survival of fish trucked and released near the Golden Gate Bridge in Sausalito. Until six years ago, most trucked hatchery fish were released into San Pablo Bay at Mare Island near Vallejo.

The report shows that two, three and four year old Feather River hatchery fish released in Sausalito survived at a rate of 2,795 for every 100,000 released, 100% better than for fish released at Mare Island (Vallejo) which survived at 1,387/100k. The Sausalito released fish were twice as prevalent in the ocean catch as well.

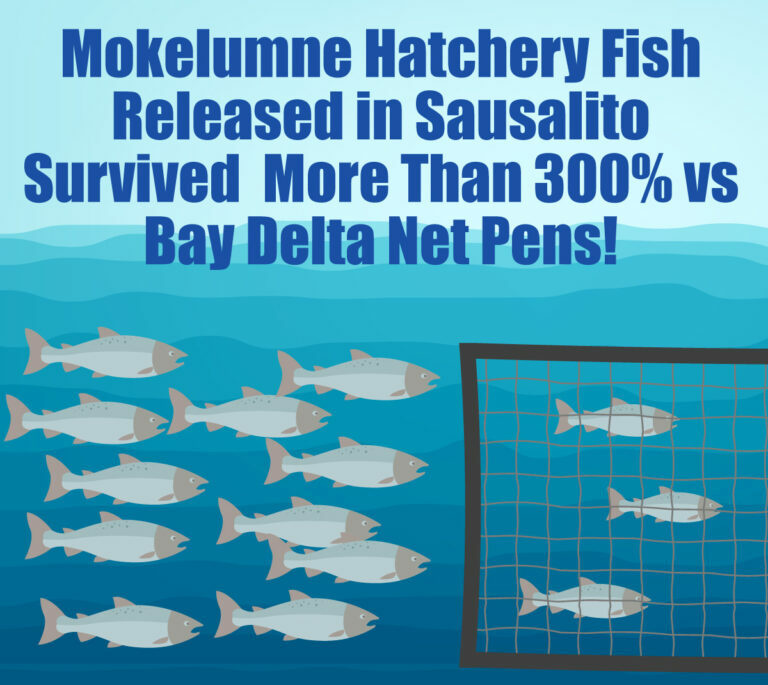

Two, three and four year old Mokelumne Hatchery fish released in Sausalito survived at 2,209 per 100k released compared to 780/100k for Mokelumne fish released from Bay Delta net pens, a better than 300% benefit!

These findings are consistent with data from the 2018 CWT report which found, “For age-2 fall-run salmon, both FRH (Feather River Hatchery) and MOK (Mokelumne Hatchery) …Golden Gate releases had the highest … escapement recovery rates for their cohort…” The same 2018 report also found, “Coastal net pen fall-run releases that took place in Pillar Point (Half Moon Bay) and … Golden Gate fall-run releases … had the highest ocean recovery rates among all release types and broods. In most instances, their ocean recovery rates were several times greater than the rates for bay/delta net pen fall-run releases of the same cohort.”

Based on the 2019 data, releases in Sausalito basically provided nearly the equivalent of adding a second Feather River hatchery, compared to survival of Feather River fish released at Vallejo.

Moving the release site for Feather River Hatchery fish from Vallejo to Sausalito caused two percent additional straying (13 percent vs 11 percent) compared to releasing at Mare Island in Vallejo.

The report also makes clear that except in really wet years, like 2017, releasing Feather River hatchery fish into the Feather River is a disastrous waste of these fish. This is consistent with the findings of the 2018 Coded Wire Tag report which found of three year old Feather River hatchery fish released into the Feather River, only 21 tags for every 100k fish released were recovered in the Central Valley compared to 619/100k for the same fish released to San Pablo Bay (Vallejo). Similarly, in 2018, coded wire tags from Feather fish released to the Feather River were recovered in the ocean fishery at a rate of only 6 per 100k released versus 298 for the same fish released at San Pablo Bay.

Although hatchery fish born in 2016 and released into the Feather River in 2017 did relatively well in 2019 returns, this is the exception to the rule. Hatchery fish born in 2015 and 2017 and released into the Feather River the following year provided almost no contribution to harvest or returns to the Central Valley. By comparison, 2017 Feather River fish released at the Golden Gate that returned to the Central Valley as two year olds out-survived those released into the river by 227 to 1. This is closer to the norm for fish released into the Feather River.

Nimbus Hatchery fish, from the American River, also benefited greatly from trucking. Trucking them to Vallejo almost tripled their survival over those released into the American River (3,310/100k compared to 1,262/100k). The trucked fish enjoyed the very low stray rate of about five percent. This demonstrates that, at least for 2019 returns, trucking Nimbus Hatchery fish provided the equivalent of building a second Nimbus hatchery – and then some.

Better trucking and release sites provides a much simpler, quicker and politically less complicated solution to increasing fish production than building new hatcheries.

The extremely wet spring of 2017 greatly boosted Coleman hatchery fish and upper Sacramento Basin natural salmon

As would be expected, that very wet spring in 2017 greatly boosted survival of both hatchery and natural salmon born in 2016 that returned in 2019. Where this is most apparent is in the strong contribution of Coleman hatchery fish to the fishery AND in the large number of naturally spawned adult fish that returned throughout the Central Valley in 2019. The ocean fishery catch was about 55 percent hatchery fish. The other 45 percent were natural born fish that enjoyed the good outmigration conditions in the wet spring of 2017, underscoring the benefit and value of good spring flows towards boosting survival of both Coleman fish and upper Sacramento Basin natural born salmon. The 45 percent natural fish compares to an average of 29 percent natural fish on the spawning grounds since 2010.

Of all hatchery fish, Coleman fish have the greatest distance and most obstacles to navigate from their upper Sacramento Basin homes to the ocean and back. Coleman fish in some ways can be considered a surrogate for natural born juvenile salmon emigrating from the upper Sacramento basin which are confronted with avoiding the same heavy predation in their trip from Central Valley rivers.

Coleman Hatchery fall-run fish released at the hatchery had the highest contribution (14%) to the total 2019 Central Valley escapement, or returns. This is tied to the fact that Coleman produces more hatchery salmon than any other hatchery but it also argues strongly for water policies that make flows available to Coleman fish even in dry years.

In 2019 California had a shot at reestablishing a vital, robust, natural origin fishery in the upper Sacramento Basin based on return of wild born fall run fish that survived due to the wet winter/spring of 2016/17. As the report says, “Fall-run escapement in the upper Sacramento River mainstem was dominated by natural-origin salmon.” Water management practices have since wiped out this gain in wild productivity.

Winter run survival was off the charts high in 2019, clearly due to the increased water they enjoyed in the river in 2017. They returned to the Sacramento River at a rate of 1,896 per 100,000 released, the highest numbers since 2006. If we had 2017 type of flows every year, these fish would probably be removed from the Endangered Species list in short order. Nothing like giving them just a little bit of water….

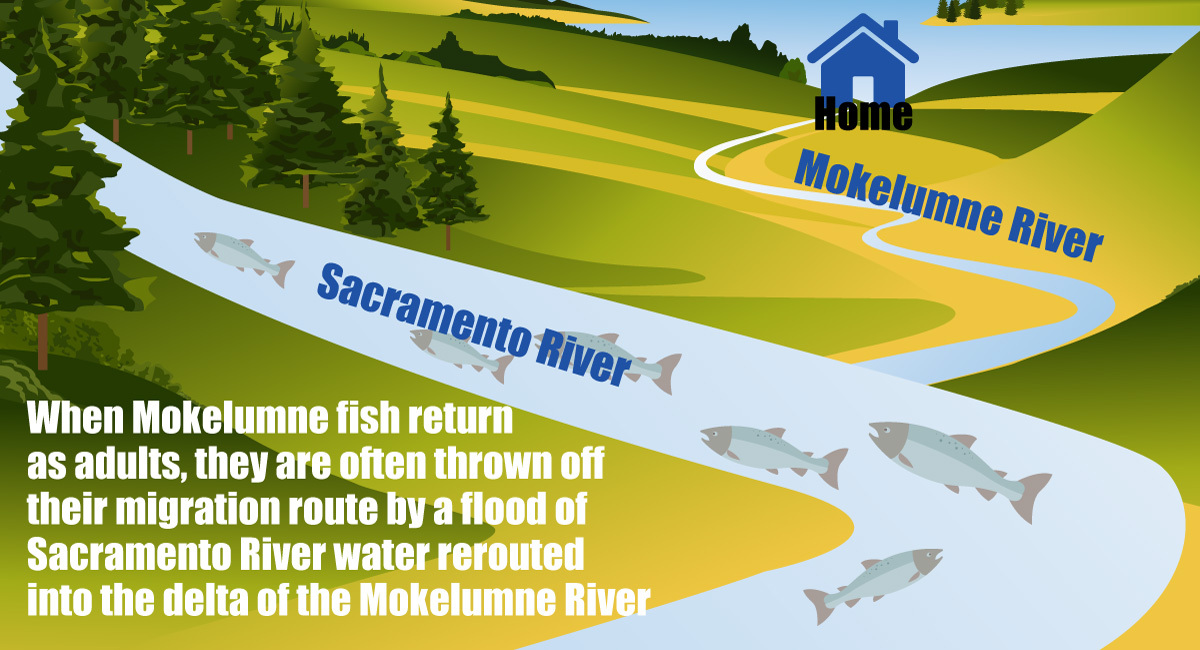

Plumbing blocks some fish from finding their way home

he report makes clear that fish from the Mokelumne hatchery have a very hard time finding their way home no matter where you release them. These fish have to be trucked to release sites in the west Delta because their natural outmigration route leads directly past the Delta pumps. When Mokelumne fish return as adults, they are often thrown off their migration route by a flood of Sacramento River water rerouted into the delta of the Mokelumne River (by the federal Bureau of Reclamation’s Delta Cross Channel). This confuses them and undermines their ability to find their way home. This is further borne out by data showing that Feather River and Nimbus (American River) fish that were released at similar locations to the Mokelumne fish have much, much lower stray rates. Both the Feather and American rivers are tributaries of the Sacramento. Bottom line: it’s not the fault of the trucking that Mokelumne fish stray…. it’s the rerouting of flow through the Delta that interferes with the salmon’s ability to find its way home.

Feather River trucked fish good for in-river fishery

If you like to catch big fish in the Feather River, consider this finding; of all four year old fish returning to the Central Valley in 2019, those from the Feather River hatchery that were trucked to Vallejo returned at the highest rates.

In 2019, after Coleman fish, Feather River hatchery fish trucked to Sausalito provided the most total fish to river anglers throughout the Sacramento Basin, followed by Feather River hatchery fish trucked to Vallejo.

In addition to the huge benefits of trucking, the report suggests credit needs to be shared with the hatchery managers at the Nimbus Hatchery. The report shows that the fish they’re now raising are strong and healthy, finding: “Ocean recovery rates for age-3 NIM fall-run releases were much higher than has previously been observed, and the bay/delta (Vallejo) releases from that brood had the highest ocean recovery rate of any release type analyzed in this report. The ocean recovery rates for both age-3 NIM bay/delta and in-basin releases were much higher than has been observed in any bay/delta or in-basin release group, respectively, from any CV hatchery since the CFM program was fully implemented.”

Another takeaway from the 2019 report is a curious note about the highly publicized rice field salmon experiments. The report found, “Releases that were part of the Knaggs Ranch rice field study have been excluded from this report, as there was only one inland recovery (an age-4 fish released as part of an in-river control group) and no ocean recoveries in 2019.”

Coastal net pens used in Half Moon Bay and Santa Cruz for acclimating and releasing Mokelumne fish showed much higher survival compared to Mokelumne fish released at Sherman Island near Antioch in the Delta. Coastal net penned two year olds that returned in 2019 outnumbered those released in the Delta by 5 to 1.

Takeaways

In addition to the need to mitigate for the loss of salmon to habitat destruction, and now drought, the common sense duty to maximize return on investment in our natural resources clearly argues for moving all or at least most releases of hatchery fish from Vallejo to areas in or near Sausalito or other west SF Bay sites. The data from 2019 and other years shows this basically provides the equivalent of doubling the number of salmon hatcheries, as measured by the number of salmon that survive to adulthood, contribute to the fisheries, and return to the Central Valley.

Another key takeaway is the waste in releasing salmon directly into the Feather River in all but the very wettest years. Yet another takeaway is there appears to be something fundamentally missing in the rice field rearing of salmon since all of the fish reared there in 2017 were never seen again.

The changes to release practices suggested above can be made with no or little additional costs to mitigators or the state and will greatly boost the number of salmon surviving to adulthood and the economic wellbeing of thousands of Californians (and Oregonians) who benefit from our salmon resource.

GGSA president John McManus is a long-time salmon fisherman and salmon advocate. He comes from a varied background that includes ten years of commercial salmon fishing in southeast Alaska, 15 years producing news for CNN and more recently, 11 years doing publicity and organizing for the public interest environmental law firm Earthjustice. Work at Earthjustice included organizing and publicity supporting restored salmon fisheries in the Columbia, Klamath and Sacramento rivers.

A San Francisco native, Muni Pier and Lake Merced were the places where he first learned to tie a fishing line, bait a hook, and cast. He’s a long time member of the Coastside Fishing Club and keeps a boat part of the year in Half Moon Bay.

From the 1970s on he spent a lot of time in the north coast salmon communities of Bodega Bay, Pt. Arena, Fort Bragg and Eureka. As salmon runs declined in the 1990’s, he got a front row seat to the demise of these communities, something that fuels his advocacy for salmon and salmon communities to this day.

The Golden Gate Salmon Association is a coalition of salmon advocates that includes commercial and recreational salmon fisherman, businesses, restaurants, a native tribe, environmentalists, elected officials, families and communities that rely on salmon.

GGSA’s mission is to restore California salmon for their economic, recreational, commercial, environmental, cultural and health values.

Currently, California’s salmon industry is valued at $1.4 billion in economic activity annually in a regular season and about half that much in economic activity and jobs again in Oregon. The industry employs tens of thousands of people from Santa Barbara to northern Oregon. This is a huge economic bloc made up of commercial fishermen, recreational fishermen (fresh and salt water), fish processors, marinas, coastal communities, equipment manufacturers, the hotel and food industry, tribes, and the salmon fishing industry at large.

Photos

Website Hosting and Design provided by TECK.net